od@mininginsight.mn

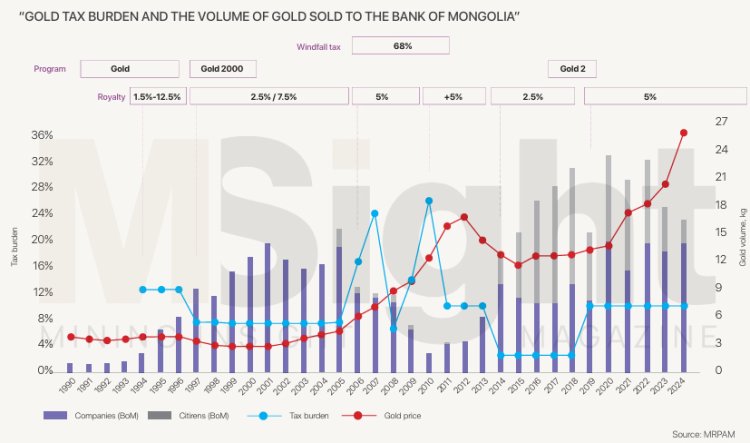

This chart illustrates how the legal and regulatory frameworksboth current and pasthave directly impacted gold production in Mongolia. Key examples include the “68% Windfall Tax,” the so called “Longnamed Law,” and provisions of the “Progressive Tax Law.” Fluctuations in the legal and regulatory environment, the resulting pressures, and taxrelated burdens have all played a decisive role in shaping gold extraction and supply. The initial adoption of the Minerals Law coincided with the implementation of the first Gold Program, which is seen as a key factor in its successful launch. The 1994 Minerals Law set the royalty (Minerals Royalty Tax, or MRT) rate at between 1.5% and 12.5%. Three years later, at the start of the “Gold 2000” program, the law was amended to set the MRT at 2.5% for hard rock deposits and 7.5% for placer deposits, significantly reducing the tax burden. This favorable taxation regime remained stable until 2005.

However, in 2006, a revised version of the Minerals Law established a flat 5% MRT, and at the same time, the infamous “68% Windfall Tax” was introduced, sharply increasing the tax burden on gold producers. During those two years, global gold prices were continuously rising. A populist narrative took hold in political circles, claiming that the country was not benefiting from the price surge. This led to the enactment of the Windfall Tax Law, which imposed a 68% tax on gold sold above $500 per ounce. Although this increased government revenue, it placed a heavy burden on mining companies, causing a sharp decline in the volume of gold sold to the Bank of Mongolia and commercial banks. As a result, the country’s foreign currency reserves suffered. In 2008, the law was revised to increase the tax threshold to $850 per ounce.

Although the Windfall Profits Tax Law was eventually repealed, the Minerals Law introduced a new provision that imposed an additional royalty of up to 5% on gold sold above $900, marking the peak of the sector’s tax burden in 2010. Over a seven-year period of continuously rising global gold prices, Mongolia imposed its heaviest taxes during five of those years. At the same time, Parliament passed Law on regulation for compliance with the Law on prohibition of mineral exploration and mineral mining at headwaters of rivers, protected zones of water reservoirs and forest fund areas. This law, known colloquially as the “Long-named Law,” added another layer of pressure on gold producers, beyond just taxation. It prohibited mineral activities in forest areas forming the headwaters of Mongolia’s rivers and the protected zones of water basins, covering roughly 25% of the country’s territory. This legal change became one of the most consequential and controversial in the history of Mongolia’s gold sector, affecting hundreds of mining licenses. The issue remains unresolved today, in part because the government has been unable to compensate license holders for canceled permits, leading to ad hoc regulatory adjustments.

Although the Windfall Profits Tax Law was eventually repealed, the Minerals Law introduced a new provision that imposed an additional royalty of up to 5% on gold sold above $900, marking the peak of the sector’s tax burden in 2010. Over a seven-year period of continuously rising global gold prices, Mongolia imposed its heaviest taxes during five of those years. At the same time, Parliament passed Law on regulation for compliance with the Law on prohibition of mineral exploration and mineral mining at headwaters of rivers, protected zones of water reservoirs and forest fund areas. This law, known colloquially as the “Long-named Law,” added another layer of pressure on gold producers, beyond just taxation. It prohibited mineral activities in forest areas forming the headwaters of Mongolia’s rivers and the protected zones of water basins, covering roughly 25% of the country’s territory. This legal change became one of the most consequential and controversial in the history of Mongolia’s gold sector, affecting hundreds of mining licenses. The issue remains unresolved today, in part because the government has been unable to compensate license holders for canceled permits, leading to ad hoc regulatory adjustments.

Under Law on regulation for compliance with the “Long named Law,” the government adopted Resolution No. 120 in 2015 to approve “Regulation on the revocation of special licenses granted in river headwater areas, implementation of relevant measures in licensed areas where mining has commenced within ordinary protection zones of water basins, and the enforcement of environmental rehabilitation” allowed for completion of mining and reclamation activities in regularly protected zones of water basin areas where extraction had already begun. It established a procedure requiring companies with licenses in these areas to enter into five-party agreements to conduct responsible mining and environmental rehabilitation. This regulation was aimed at allowing the responsible completion of mining operations and environmental rehabilitation in sites that had already been disturbed prior to the law’s enforcement, and it has remained in effect for the past 10 years When the “68% Windfall tax” was repealed, the overall tax burden dropped to levels comparable to the 1990s. In 2014, the sector’s main legal framework was further revised to set the MRT at just 2.5%, marking the lowest tax period in the industry’s modern history. This tax regime remained in effect for five years and provided strong support for gold producers. In 2019, the MRT was increased again to 5%, and the additional rate was eliminated. During the low-tax years, gold supply and Bank of Mongolia purchases steadily increased. In contrast, periods of high taxes and legal pressure effectively “brought the gold sector to its knees.”

Mining Insight Magazine, June & July 2025 №06, 07 (043, 044)