O.Batbold

As global trends in transparency evolve, corporate accountability is gaining greater importance. In Mongolia, reporting on human rights and environmental issues in business operations remains a relatively new practice. In this context, the European Union funded “Agents of Change: Youth and Media for Responsible Business Practices” project is being implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The project seeks to raise awareness among media outlets and journalists about human rights abuses and environmental damage caused by irresponsible business practices, while also promoting good practices of ethical and transparent companies that respect human rights in their operations including supply chains and minimize their negative impacts on environment. This article was prepared within the framework of the “Agents of Change” project.

Violations of the Right to Live in a Healthy and Safe Environment

While the mining sector contributes substantially to Mongolia’s social and economic development, weak enforcement of state policies and regulations, coupled with irresponsible mining operations, has placed significant pressure on fundamental human rights, according to the National Human Rights Commission of Mongolia (NHRCM).

The NHRCM’s 23rd Report on the Situation of Human Rights and Freedoms in Mongolia addresses seven key issues. Two chapters — “The Right to Live in a Healthy and Safe Environment” and “The Rights of Human Rights Defenders Working in Civil Society and Environmental Fields” — specifically highlight violations linked to mining activities. This article focuses on the first: the right to live in a healthy and safe environment.

The report warns that in mining-affected areas, environmental degradation and violations of citizens’ rights to health and safety are widespread. These violations also undermine other fundamental rights — including the rights to health protection, traditional pastoral livelihoods, nomadic culture, and access to information. The NHRCM examined these issues in Khovd, Dornogovi, Dornod, Umnugovi, and Orkhon provinces.

Impact of Mining Dust on Local Communities

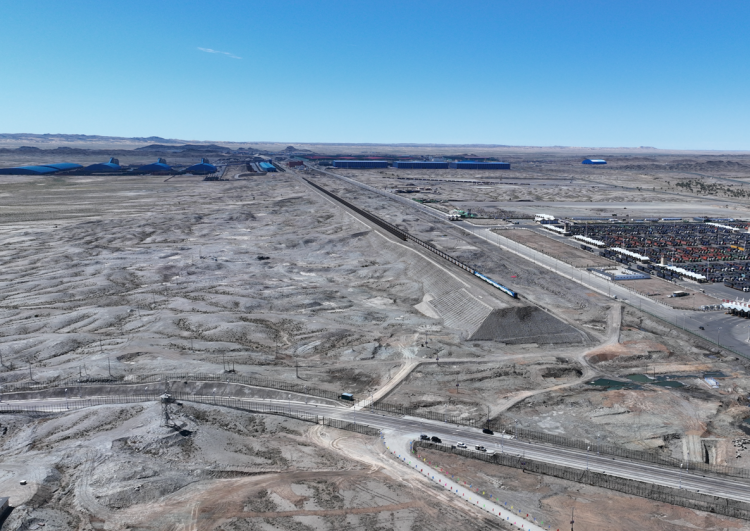

The report notes that dust, noise, and vibration from extraction, blasting, and transport in mining regions not only degrade the environment but also harm human health. Residents near Khovd’s Khushuut coal mine, Umnugovi’s Tsogttsetsii (Tavan Tolgoi) mines, and Erdenet Mining Corporation have filed complaints about dust pollution and its long-term health effects.

Although some companies have taken measures to reduce dust, the NHRCM concludes that progress remains limited. In Dornogovi’s Dalanjargalan soum, 80% of surveyed residents said the air was “heavily polluted,” showing how emissions, waste gases, and noise from mining severely affect daily life.

Water Use, Water Quality, and Emerging Risks

The report found that water scarcity and contamination are the greatest concerns for local residents. Nearly 65% of respondents said that mining had “significantly polluted” drinking water. In the Gobi region, increasing extraction of deep groundwater by large mining operations has raised fears among herders of losing access to water for household and livestock use.

Open discharge and accumulation of mining wastewater have harmed livestock health and degraded animal products, leading to economic losses. Moreover, newly drilled wells often require herders to pay for electricity or diesel fuel to pump water, adding to financial pressures. Although the mining sector’s total water consumption is lower than that of agriculture, the report identifies groundwater extraction in the Gobi as a critical risk. If mining intensifies, groundwater reserves may be insufficient by 2030.

The report emphasizes that rising water use is not only an environmental concern but also a serious threat to local livelihoods and economic rights.

Soil Contamination and Pasture Degradation

The NHRCM underscores that herders’ main difficulties arise from pasture loss and water shortages. Mining operations and infrastructure expansion have reduced grazing lands and restricted the traditional mobility of herders. Around the Tavan Tolgoi deposit and along the Gashuunsukhait road, herders struggle to graze their animals due to roads and long queues of coal trucks. In Dalanjargalan soum, the loss of pasture has forced many herders to migrate to Ulaanbaatar.

Additionally, waste and debris — such as tires, bottles, and plastic — discarded along mining routes pollute the soil and endanger livestock. In some areas, arsenic and heavy metal levels in soil and water exceed permissible limits many times over, directly violating people’s right to health and life. For example, Petro China Daqing Tamsag LLC was found to have caused soil and water contamination by discharging petroleum waste, according to expert findings. Researchers warn that such pollution poses long-term risks to human health, livestock, and food safety.

Lack of Transparency and Violation of the “Right to Know”

The NHRCM found that residents in mining-affected areas often face restricted access to environmental information. In Dalanjargalan soum, 74% of respondents said they had never received any information from mining companies, and another 14% said their requests for information had been denied. In total, 88% reported having no access to data about nearby mining activities.

Further analysis of public records revealed that: Most mining projects do not conduct human rights or social impact assessments, Environmental management plans and monitoring reports are not publicly available, State databases are incomplete, and Most companies lack online transparency.

The report concludes: “Local residents lack information about mining operations in their territories, are excluded from decision-making processes, and have no opportunity to participate in or influence such decisions.” This represents a clear violation of the right to information. Decisions made without public participation breed distrust and conflict, which can easily escalate into social unrest.

Conclusion

Summarizing the NHRCM’s findings, it is clear that environmental degradation and human rights violations remain intertwined in the mining sector. Depleted pastures and dwindling water sources threaten the foundations of nomadic herding, putting both economic and cultural rights at risk.

While many mining companies operate responsibly, not all do — and this disparity is a serious warning. Mongolia must move toward greater accountability, transparency, and openness in mining governance. Only by aligning economic development with human rights and environmental protection can the country safeguard its nomadic heritage while pursuing sustainable growth.

As long as mining remains the backbone of Mongolia’s economy, its operations must not endanger citizens’ health, living conditions, or traditional livelihoods. True development is measured not only by economic growth but by its consistency with human rights and quality of life. Ensuring that citizens’ voices influence policies — and fostering responsible mining that respects both people and the planet — will secure not only economic stability but also a more sustainable future for Mongolia.