In the three years since the first Critical Minerals Seminar, the organizer-the Mongolian Critical Minerals Association (MCMA)-has made considerable progress in its operations. In fact, “considerable” may be an understatement. They have officially identified Mongolia’s first 11 critical minerals, and have also developed Critical Minerals Development Roadmap, outlining goals through 2035.

A TIMELY CONFERENCE

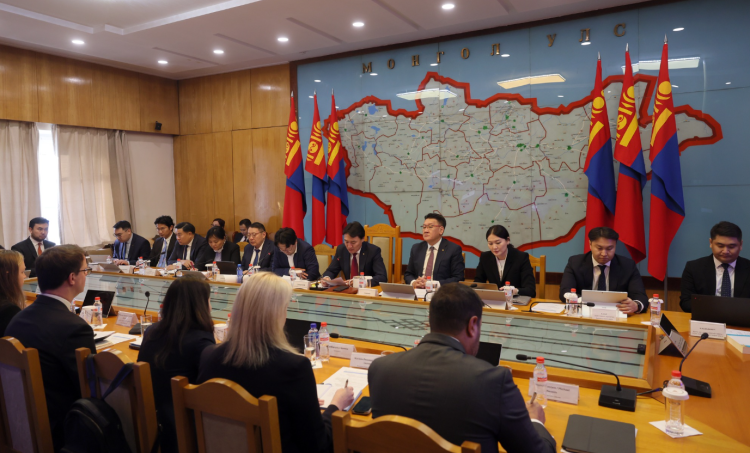

The third Critical Minerals Seminar, held on May 29, 2025, under the theme “Critical Minerals: Trends in Mongolia and Globally,” brought together representatives from government, the private sector, and international researchers, continuing a now-established tradition. Presentations focused on geopolitical involvement and featured contributions from both Mongolian companies and researchers from the United Kingdom (UK). In Mongolia, private sector involvement in critical minerals-excluding copper-is still in the early stages. By contrast, representative from UK, critical raw materials expert Gavin Harper, emphasized how his country meets domestic needs through mining, imports, and processing of secondary raw materials. Creating a list of critical minerals typically takes 1 to 1.5 years in many countries: for example, the European Union has taken about a year, the U.S. 1–1.5 years, and Canada under a year. These countries have regulations allowing them to revise their lists within a three-year timeframe. Since announcing initial 14 critical minerals in 2011, the EU has now expanded its list to 34. Mongolia is likely to adopt a similar approach, as suggested by the feedback gathered over the past three years. One may ask: why does Mongolia need a roadmap for critical minerals? This article aims to shed light on that question. From a journalist’s perspective, restoring confidence among foreign investors and companies working in this field seems inevitable. The roadmap was presented during the third seminar and is expected to be submitted to Parliament’s Spring Session in collaboration with the Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources, giving the initiative more formal weight.

Mongolia lies between two global powers. One of them, China, plays a big role in the global critical minerals mining and processing sectors. The country has long used rare earth elements considered critical minerals-as a tool in geopolitical strategy. This trend continues, with China leading globally in exploration, research, and technology development for critical minerals. Russia follows closely. Since the beginning of the year, Russia has announced ambitious goals in this sector. The country aims to develop its resource base through 2050 and announces the possibility to eliminate imports of 12 key minerals by 2028, including lithium, niobium, tantalum, rare earth elements, zirconium, manganese, tungsten, molybdenum, rhenium, vanadium, fluorspar, and graphite. Notably, Russia plans to increase lithium carbonate production from 27 tonnes in 2023 to 60,000 tonnes by 2030 and sees potential cooperation with the U.S. in rare earth elements. Thus, our country, keeping pace not only with its neighbors but also with other nations, identified specific critical minerals and developed a roadmap. This aligns with the 2024–2028 Government Action Plan, which aims “to enhance Mongolia’s role, participation, and bilateral/multilateral cooperation mechanisms in the critical minerals sector”. Researchers at the seminar emphasized that the dominance of the private sector in Mongolia’s critical minerals field is a key strength.

Mongolia lies between two global powers. One of them, China, plays a big role in the global critical minerals mining and processing sectors. The country has long used rare earth elements considered critical minerals-as a tool in geopolitical strategy. This trend continues, with China leading globally in exploration, research, and technology development for critical minerals. Russia follows closely. Since the beginning of the year, Russia has announced ambitious goals in this sector. The country aims to develop its resource base through 2050 and announces the possibility to eliminate imports of 12 key minerals by 2028, including lithium, niobium, tantalum, rare earth elements, zirconium, manganese, tungsten, molybdenum, rhenium, vanadium, fluorspar, and graphite. Notably, Russia plans to increase lithium carbonate production from 27 tonnes in 2023 to 60,000 tonnes by 2030 and sees potential cooperation with the U.S. in rare earth elements. Thus, our country, keeping pace not only with its neighbors but also with other nations, identified specific critical minerals and developed a roadmap. This aligns with the 2024–2028 Government Action Plan, which aims “to enhance Mongolia’s role, participation, and bilateral/multilateral cooperation mechanisms in the critical minerals sector”. Researchers at the seminar emphasized that the dominance of the private sector in Mongolia’s critical minerals field is a key strength.

TERMINOLOGY AND UNIFIED UNDERSTANDING

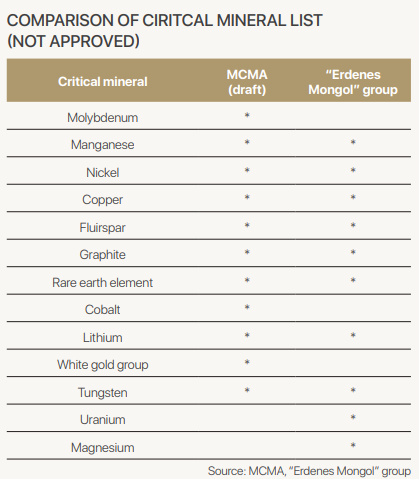

Variations in terminology-such as “critical natural resources,” “critical elements,” and “critical minerals”-are also used. Regardless of wording, it’s important for Mongolia to adopt a unified understanding. The government’s 2024–2028 action plan uses the term “chukhal ashigt maltmal,” which is likely to remain in use for the foreseeable future. It’s also important to consider clarity for the general public. Meanwhile, the state-owned enterprise “Erdenes Mongol” group refers to these as “critical minerals” in English and exchanges information with MCMA. The group has designated copper, rare earth elements, lithium, graphite, magnesium, manganese, nickel, tungsten, fluorspar, and uranium as critical. However, some sector professionals offer a different view. T. Munkhbat, President of the Mongolian Geological Association, pointed out potential issues with the term “ashigt maltmal” (literally “useful mineral” or “ore”) and recommended using “critical minerals” or “critical elements”instead. He said, “Not a single item on the list is technically an ‘ashigt maltmal.’ We should use ‘minerals’ to ensure proper understanding internationally. There are over 6,000 minerals in the world. If we call all of them ‘ashigt maltmal,’ it becomes problematic.” This issue has likely been considered not only by officials but also by policy drafters and stakeholders in the sector.

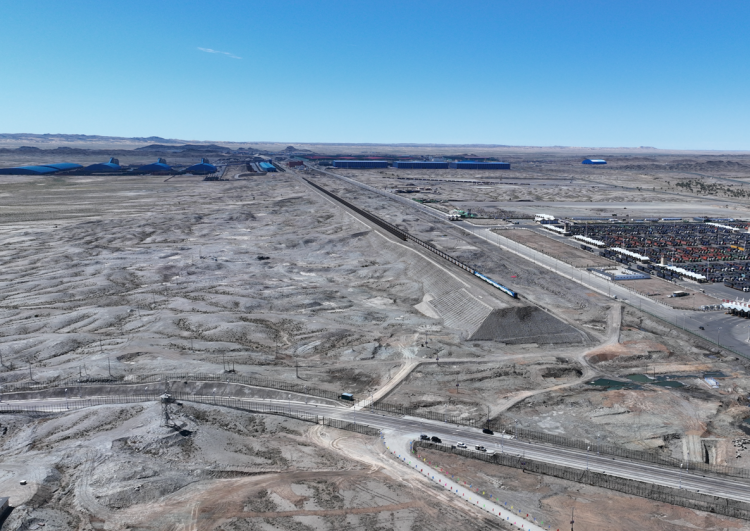

NO NEED TO SEARCH FOR CRITICAL MINERALS MARKET - FOR MONGOLIA IT IS RIGHT NEXT DOOR

Although not yet officially approved, Mongolia exported four of the 13 critical minerals identified by the MCMA in 2024. The majority of the total 3 million tons of critical minerals were purchased by China. In the near future, Mongolia is expected to confirm reserves and begin utilization of deposits containing rare earth elements, lithium, and uranium-minerals for which China currently leads global production and consumption. This means Mongolia does not need to look far for an international market. However, if Mongolia exports its critical minerals to other countries via Chinese territory, new conditions may emerge requiring a share for the transit country. In addition to China, countries such as Russia, South Korea, and Luxembourg also imported Mongolian critical mineral products last year. If Mongolia establishes a clear policy on critical minerals, there is strong potential to expand its list of importing countries and strengthen international relations.

THE UK’S SECONDARY RAW MATERIAL PROCESSING DIFFERS FROM MONGOLIA

In 2021, the United Kingdom identified 18 types of raw materials as critical to its economy and national security-similar to other countries. The UK is now focused on reducing its heavy reliance on imports. After exiting the European Union, the country had to independently define its own critical mineral strategy. However, given its proximity to Europe, mutual influence between the two remains inevitable in this sector. While the UK’s dependency on imports is likely to continue, it is taking steps to reduce this by reassessing domestic mineral reserves, launching new exploration efforts, and placing greater emphasis on the recycling and processing of secondary raw materials. Although Europe, including the UK, consumes about 30% of the world’s critical minerals, it extracts only 2–3% of these resources from its own territory. This creates a condition quite different from Mongolia, which follows a different path of exploration–extraction–processing– export. In conclusion, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has projected that global demand for critical minerals will double by 2030. Given this growing demand, discussions around this topic will only intensify. Mongolia now has a real opportunity to diversify its economy and mining exports based on global needs. Unlike in previous years, the country has now developed a roadmap for its critical minerals sector. What remains is to decide on it.

“WE AIM TO DEVELOP MONGOLIA’S NEW GENERATION OF MINING”

G. SURAKHBAYAR, Board Member of the Mongolian Critical Minerals Association (MCMA) NGO

We interviewed G. Surakhbayar, Board Member of the Mongolian Critical Minerals Association (MCMA) NGO, about the association’s activities and the Critical Minerals Development Roadmap presented during the third annual seminar “Critical Minerals: Trends in Mongolia and Globally.” Our association was founded in 2022 with the vision of developing Mongolia’s mining sector from a fresh perspective-one focused on building a new generation of mining. Critical minerals are inherently linked to issues such as green development, energy transition, and climate change. With this in mind, we’ve organized extensive seminars on critical minerals policy over the past three years-and we will continue to do so. Beyond these multi stakeholder seminars, we also actively participate in international events and conferences, expand our foreign and domestic relations, and conduct training and research within Mongolia. Countries around the world are formulating and implementing their own national, regional and continental critical minerals strategies, creating and updating their mineral lists. The European Union (EU), for instance, has passed legislation on critical minerals. The United States of America (USA) and Canada have expanded their lists, and countries like India have adopted such lists for the first time. After studying these strategies and policies, we concluded that Mongolia must align its long-term development policies-including Vision 2050, the New Recovery Policy, and the Government’s Action Plan-with the growing need to develop its mining sector through a critical minerals lens. So, we began working to answer the question: What should Mongolia’s strategy be? Should it be independently implemented? In 2024, from our position as the sector’s NGO, we proposed a list of around 10 critical minerals, which we shared with ministries, agencies, and international partners. We’ve worked on the roadmap since last year. We realized that to move from policy, strategy, list to implementation, a structured and time-phased plan-short-, medium-, and long-term-was needed. It’s also essential to speak in terms of the upstream, midstream, and downstream of the mining value chain. Mongolia’s policy is to transition from raw extraction to processing. But where are our policies for advanced and secondary processing? Since the 2010s, government action plans have mentioned high-tech mineral processing, yet the definitions and mechanisms remain vague or nonexistent. Traditionally, Mongolia has created mineral-specific programs for gold, copper, fluorspar, etc. Some succeeded, others didn’t. But focusing on single minerals is no longer practical from an international trend, innovation or efficiency standpoint. So, we developed our roadmap based on sub-sectors of critical minerals. We’ve always defined our sector as geology, exploration, mining, and heavy industry. We have initiated thise comprehensive document on how to integrate next-level hight technology, or in international terms - upstream, midstream, and downstream side. In other words, we have initiated this comprehensive roadmap for Mongolia’s critical minerals development through 2035. This roadmap essentially consists of four main components.. First, Foundational Issues: Geology, Exploration, and Reserves. We must discuss how to advance geology, digitize the results of 50–60 years of geological exploration, and make that data more accessible to domestic and international investors. The roadmap addresses how the recent multi-billion tugrik investments in geological surveys from the state budget are performing, whether exploration licensing is effective, and more. Secondly, Policy Stability and Institutional Capacity. Today, ministries, agencies and provinces have designated regional specialists, which is progress. However, the Mining Law has been amended 350 times in the past 19 years. For example, the Ministry of Finance can interfere in mining policy decisions. Policy and institutional stability must go beyond one ministry or agency-they involve capacity, budgeting, technology, innovation, partnerships, foreign/ domestic relations, public-private cooperation, and investment. Whether it’s traditional or new generation mining, critical minerals must be treated with the same stability and importance as foreign policy. Foreign policy in Mongolia is untouchable and consistent. But the mining sector-the one that generates revenue-is constantly politicized and micromanaged. Thirdly, Legal and Regulatory Environment . When we mention legal issues, most think only of the Mining Law. But what about investment, responsible mining, or environmental assessments? Policy concerns extend beyond mining law. We also lack legal frameworks for beneficiation and processing plants, yet operations are licensed. How can business thrive in such uncertainty? We’ve talked about a heavy industry law for 15 years, but it still doesn’t exist-meaning the midstream can’t develop. The current law only addresses upstream: geology, exploration, and licensing. Environmental and human rights issues are also linked. If we reduce the conversation to just the Mining Law, we risk public and political rejection. With constitutional amendments already made, if we’re serious about developing high-tech mineral industries-as stated in our policies-we must clarify the legal environment needed for that. Fourth, Infrastructure. Infrastructure is a challenge for mining sectors worldwide. Projects are usually in remote areas. For instance, imagine opening a mine in Deren soum of Dundgovi Province. Heavy trucks can’t use public roads, so companies are told to build their own. But not every project can afford that. Some good examples exist: MonEnCo built a paved road from Khovd’s Khushuut mine to the border; Oyu Tolgoi and Bold Tumur Eruu Gol have also built their own infrastructure. But while some private companies manage, others can’t. Since the government collects taxes, it should contribute to infrastructure development. What should the state provide, and what should companies cover? This needs to be clearly outlined in the roadmap. Lack of policy coordination is our mistake. Our success will lie in fixing that through coherence. Because of this gap, companies can’t expand. That’s why MCMA’s roadmap emphasizes coordination and outlines what is happening at each stage of the sector-for stakeholders, policymakers, and decision makers. We’re also trying to estimate how much investment is needed to implement the roadmap. That way, we can present clear figures for the state budget and communicate accurate funding needs to foreign and domestic partners. During our third seminar, we introduced this roadmap. It was co-hosted by MCMA in collaboration with the National University of Mongolia, MUST, the German-Mongolian Institute for Resources and Technology, government agencies, private companies, and international organizations. Since then, we’ve received feedback. Some believe the roadmap is premature or unnecessary. Others have made valuable suggestions: to improve the geology section, to increase international relevance, to digitize the framework. We thank all our partners and collaborators. We believe progress doesn’t come by sitting idle-it comes through persistent work. We’re confident that we can solve at least one major issue by moving forward deliberately.

Mining Insight Magazine, 2025 №06, 07 (043, 044)