ABSTRACT

Mongolia is one of the ten most resource rich countries in the world. In the south of the country, the Gobi Desert, there are gigantic deposits of copper, silver, gold, coal, fluorspar and other raw materials that are among the largest in the world. Mongolia's geology, which is characterized by diverse mineral rich strata from the Precambrian to the Quaternary, forms the basis for the country's mining potential. Above all, the country has an abundance of REEs, which are essential for cuttingedge technologies and the energy transition. This report analyses the geological formations that underlie Mongolia's resource wealth, highlighting carbonatite and peralkaline granitic rocks as prolific sources of REE mineralization. Important deposits such as the Mesozoic carbonatites Mushgia Khudag and Khotgor and the Devonian peralkaline granites Khalzan Buregtei emphasize the economic potential of these resources.

ECONOMY

Mongolia is undergoing a structural transformation driven by the mining boom, the increase in foreign investment, partly financed by foreign loans, and the growing complexity of the private sector. GDP per capita fluctuates around USD 5,700, which puts the country in the category of upper middle income countries according to the World Bank's classification. As it is a miningdriven economy, the main growth has been fueled by the export of commodities such as gold, copper and cashmere. The mining sector contributed an average of 25.7% to Mongolia's GDP in the last three years. In 2023, Mongolia exported to 81 countries and imported from 159 countries around the world (Mongolian customs service 2024). Mongolia's most important trading partner was China (72.25%). The most important importers of Mongolian products were China (91.56%), Switzerland (4.39%), South Korea (0.83%), Russia (0.73%) and Italy (0.65%). Mongolia's most important import partners were China (40.55%), Russia (25.81%), Japan (7.75%), South Korea (4.49%) and USA (3.04%).

CHALLENGES IN COOPERATION WITH MONGOLIA

Economic challenges

Although Mongolia is considered a fastgrowing economy in terms of GDP, the country is failing to diversify its economy. Mongolia's economic growth and government revenues are heavily dependent on mining. This dependence on extractable natural resources has come at a cost. According to the ranking of the World Competitiveness Ranking 2024, Mongolia is the 61st most competitive nation in the world out of 67 countries1. This situation leads to further challenges such as brain drain, increase in foreign debt, corruption, etc., which have a negative impact on the social well being of the population.

Challenges for the development of the transport and logistics sector

Mongolia faces challenges in the areas of international trade, transit and socioeconomic development due to the lack of territorial access to the sea and the resulting remoteness or isolation from world markets as well as high transit costs. According to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Mongolia has the right of access to the sea and freedom of passage. Mongolia has 4 ports in Russia and 3 ports in China for access to the sea. The most important port is Tianjin in China, through which 95% of shipments to and from Mongolia pass.

International connectivity - rail connection

Ulaanbaatar Railway (UBTZ) is the only railroad company in Mongolia that owns the main line on the territory of Mongolia and is authorized to operate on the international railroad corridor. The TransMongolian Railway is connected to the TransSiberian Railway Corridor (OSJD Corridor No. 1) at the railroad junction of UlanUde, Russia, and to the Chinese Railway via Ereen hot, China (Figure 2). The current capacity of the UBTZ, due to the lack of connections to the mining areas, the limited number of rolling stocks, locomotives, throughput capacity of the railroad hubs and logistics facilities at the border and in Ulaanbaatar, is the biggest challenge for the railroad sector when it comes to expanding operations to meet market demand.

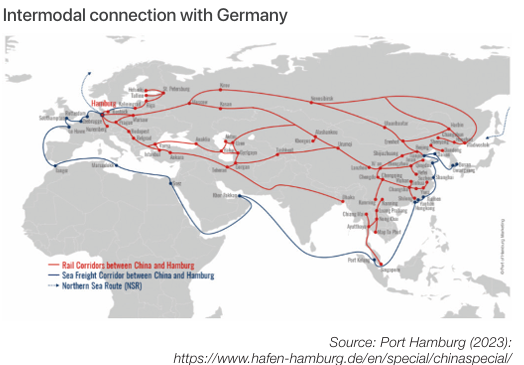

Transport routes to and from Germany

Rail connections are possible via China and Russia. There are both searail and searoad transports between Germany and Mongolia via the port of Tianjin in China. The containers between Germany (Port of Hamburg and Bremerhaven) and China (Tianjin) are shipped by sea. This currently takes 35 days. Containers between Tianjin and Ulaanbaatar can be transported either by road or rail. Rail transportation between Tianjin and Ulaanbaatar usually takes 23 days. Road transportation on this route is rarely used and is carried out exclusively by Chinese forwarding companies.

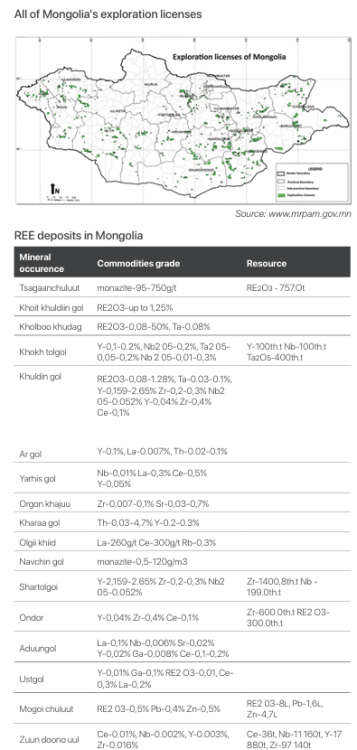

RARE EARTHS IN MONGOLIA

Despite the lack of extensive exploration across Mongolian territory, significant REE concentrations have been identified in areas such as Khanbogd, Kharzanbüregtei, Lugii River, Mushgia Khudag, Khotgor, Shar Tolgoi, Mushgia and Ulaan Del. These include five different deposits, 71 occurrences and over 260 mineralized areas.

Carbonatites: 1Mushgia Khudag; 2Khotgor; 3Bayan Khoshuu; 4Lugiin Gol; 5Ulgii Khiid; 6Bayan Obo.

Carbonatites: 1Mushgia Khudag; 2Khotgor; 3Bayan Khoshuu; 4Lugiin Gol; 5Ulgii Khiid; 6Bayan Obo.

Peralkaline granites: 7Khanbogd; 8Khalzan Buregtei; 9Ulaan Tolgoi; 10Tsakhir;11 Ulaan Del; 12 Shar Tolgoi; 13Maihan Uul. Number 6 is a large Bayan Obo REE deposit in Inner Mongolia, China.

REE EXPLORATION LICENSES

In August 2023, Mongolia reported 983 exploration projects, most of which are privately owned. Due to the confidential nature of the exploration phase, detailed information about these projects is not accessible to companies due to legal regulations.

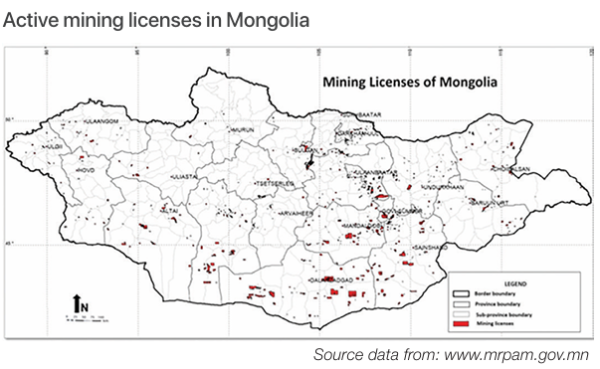

REE MINING LICENSES

In Mongolia, a considerable proportion of foreign direct investment has gone into the mining of minerals. This sector has attracted over 1,777 companies, which together hold 2,861 licenses (Fig. 14). Exploration has demonstrated the presence of uranium and thorium in Mongolian RE deposits. For example, Graupner (2012) confirmed the presence of monazite, a thoriumbearing RE mineral, in fresh samples from the Mushgai khudag area. The use of gamma spectrometry as a standard tool in RE exploration further emphasizes the presence of radioactive minerals in these deposits. In addition, traces of sulphide minerals were found in the carbonate ores of Mushgai khudag, Khotgor and Lugiin gol.

PROCESSING AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

The environmental problems associated with the mining and refining of rare earths are profound and include high resource consumption, the generation of chemical pollutants, emissions that lead to air and water pollution, the production of solid waste and the risk of radioactive radiation. Addressing these issues is essential for the sustainable sourcing of REEs.

Mining and refining

This first phase of REE ore processing comprises the mining and physical processing of the rare earth minerals. The rare earth minerals are separated from the nonvaluable minerals (gangue), resulting in a concentrated form of rare earth minerals. LREEs are mainly extracted in opencast mines, while HREEs are mainly extracted using insitu methods.

Ion absorption ores

Particularly in the case of HREEs, these ores are better suited for extraction and processing due to the ionic nature of rare earths. In particular, clay deposits with ion adsorption are rich in HREEs such as dysprosium and yttrium and exceed the concentrations in other minerals such as bastnäsite and monazite.

Chemical treatment and separation

In this phase, the REE minerals, which are generally present as fluorocarbonates and phosphates, are converted into carbonates or chlorides. They are then separated using techniques such as ion exchange or solvent extraction. This chemical processing not only removes impurities, but also increases the concentration of rare earth oxides (REOs) to around 90 %. Various reagents are used in the process, including inorganic acids (sulphuric, hydrochloric and nitric acid), alkalis (sodium hydroxide and sodium carbonate) and electrolytes (ammonium sulphate, ammonium chloride and sodium chloride).

Roasting and leaching

In the BayanObo process in Inner Mongolia (China), the REE concentrates are treated with concentrated sulphuric acid and heated in a rotary kiln. Gases are released during this process and the resulting roasting residue is leached with water to dissolve the rare earth sulphates. The solution is then neutralized, leaving a thoriumcontaining residue, and the purified leachate is precipitated with ammonium bicarbonate.

Solvent extraction and high-purity separation

The process involves further evaporation of the strip brine after hydrochloric acid stripping to recover REE chlorides. To obtain highpurity REEs, a solvent extraction is carried out, which often requires several stages, sometimes more than 100.

Reduction, refinement and purification

The final step is the conversion of highpurity REOs into REEs or rare earth metals (REMs). This includes various reduction processes of anhydrous chlorides or fluorides, REOs and the fusedsalt electrolysis of chloride or REOfluoride mixtures.

CONCLUSIONS

Mongolia's geological endowment, which is characterized by diverse mineral rich strata from the Precambrian to the Quaternary, forms the basis for the country's mining potential. Above all, the country has an abundance of REEs, which are essential for cutting edge technologies. Important deposits such as the Mesozoic carbonatites Mushgia Khudag and Khotgor and the Devonian peralkaline granites KhalzanBuregtei underline the economic potential of REE mineralization in Mongolia. Due to the high transportation volume which is required the logistics for concentrates to Germany is very complicated and long lasting. As a consequence, the processing would have to take place in Mongolia, but the impact of rare earth mining and processing on the environment is extensive and complex and requires urgent attention and remediation strategies.

Mining Insight Magazine, December 2024