Next year will mark the 20th anniversary of the revised version of the Mineral Resources Law. In other words, the law that laid the foundation for the rise of the mining sector, which has grown to become a key driver of Mongolia’s economic development, was passed 19 years ago. Additionally, the concept of “strategic deposits” was introduced, and it has been 18 years since the first 15 strategic deposits were declared. Now, the government has started a high-profile initiative to determine the state’s ownership share in strategic deposits, with the aim of fulfilling the law that was passed 19 years ago. From the perspective of the economic situation at the time and the legal framework, one could argue that the government is engaging in the largest populist move in the mining sector. However, viewing this event merely as populism or an act of pressuring private enterprises is not only superficial but also a form of misguided populism that strays from reality. Instead, it should be seen as a process that inevitably emerged and one that has unfolded according to a plan prepared in advance. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly who, when, and what was prepared, but it is possible to recall where and how it all began. Back in late 2018, the government confiscated the Salkhit deposit and used it as collateral to forgive pension loans for veterans, a move that was widely praised by the public. Then, in 2019, when amendments were made to the Constitution, the principle of ensuring the equitable and fair distribution of natural resources to all the people was enshrined, and the government’s right to hold stakes in mineral deposits was secured. From that point, it became clear that one day, a wide-ranging campaign for the state to hold stakes in mining companies would eventually begin. Perhaps that time has now come. With the passage of the Sovereign Wealth Fund Law over a year ago, the concept of strategic deposits, which had been forgotten, was solidified in the legal environment, and it became clear that companies holding strategic deposits would enter negotiations with the government. Many in the mining sector initially viewed this as an election show or a “fight among the big players.” However, a one-year period was given to large companies to assess the situation and prepare for negotiations. That time has now expired. It is certain that both Energy Resources and MAK were aware of this moment and were well-prepared for it.

WHY ENERGY RESOURCES AND MAK?

Essentially, the main focus is on the Ukhaakhudag deposit, owned by Energy Resources, and the companies owning the Nariinsukhait group of deposits, primarily MAK. Additionally, Tsairt Mineral LLC, which owns the Tsairt zinc deposit, and Boroo Gold, which owns the Boroo deposit, may be affected by the situation. Other deposits, due to their state ownership stakes, do not have any pressing issues. The three uranium deposits—Mardai, Gurvanbulag, and Dornod—and the Burenkhaan phosphate deposit are not ready for development, so the process of determining the state’s ownership share in these deposits is not considered urgent. The ownership of the Gatsuurt deposit is unclear, and the state has taken it under protection, while the state’s ownership share in the Tsagaan Suvarga deposit was decided by the Parliament 10 years ago, excluding state ownership. Other strategic deposits are under state ownership. Looking at it this way, the process of determining the state’s ownership share in strategic deposits essentially focuses on Energy Resources and MAK. The question arises as to whether there is a legal basis for determining the state’s ownership share in the Ukhaakhudag and Nariinsukhait deposits. Let’s examine the timeline. In July 2006, the Parliament passed a revised version of the Mineral Resources Law, introducing the term “strategically important mineral deposits” for the first time, and allowing the state to own between 34% and 50% of these deposits. This law came into effect in July 2007. The first instance of specifying which deposits would be considered strategic occurred in February 2007. Annex 1 of the Parliament’s Resolution No. 27 listed 15 deposits as strategically important, and the names of the companies operating at that time were also included. The initial resolution’s Annex 1 included the Tavantolgoi deposit, stating that the deposits under the special licenses of Tavantolgoi JSC, Energy Resources LLC, and Daichuke LLC would be considered. In 2018, Resolution No. 73 made an amendment, changing Daichuke LLC to ETT JSC.

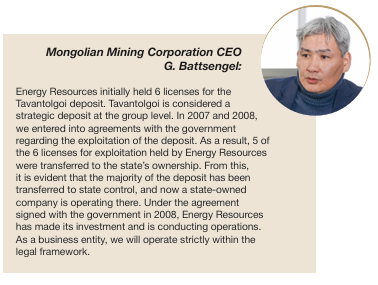

Ukhaakhudag deposit. The question is whether it is a strategic deposit or the state has the right to own a share. The first six exploitation licenses for the Tavantolgoi group of deposits were granted to Energy Resources in August 2006, as can be seen from the cadastral system of the Mineral Resources and Petroleum Authority of Mongolia (MRPAM). Prior to that, there were exploration licenses, which passed through both foreign and domestic companies until they were eventually owned by Mine Info LLC. Subsequently, Mine Info LLC, together with other investors, established Energy Resources in August 2005 and transferred the exploration licenses of Tavantolgoi to Energy Resources. The company then converted the exploration licenses into exploitation licenses in 2006. This shows that the exploration license for Tavantolgoi was transferred to Energy Resources before the amendment of the Minerals Law. However, it is important to note that before the Parliament’s decision in February 2007 to include the Tavantolgoi deposit as a strategic deposit, Energy Resources already owned the six exploitation licenses for the Tavantolgoi deposit. In other words, it means that the Tavantolgoi deposit, which was owned by Energy Resources, was later designated a strategic deposit by the Parliament, not that the strategic deposit of Tavantolgoi, which was under state ownership, was transferred to Energy Resources. Since it has been designated a strategic deposit, the state must agree on the percentage of state ownership for it to continue operations. Similar to Oyu Tolgoi, Tsagaan Suvarga, and Zuuvch Ovoo. The government and Energy Resources held multiple negotiations in 2007 to determine the state’s ownership share in the Tavantolgoi deposit. At that time, the government’s direction was not to have a stake in Energy Resources but to acquire all of Tavantolgoi’s licenses for the state. As a result, in 2008, a special agreement to transfer mineral licenses was signed, with Energy Resources transferring five of its licenses, excluding Ukhaakhudag, to the state for a nominal fee of one MNT. By transferring 96% of the total area of the Tavantolgoi deposit, or 68,000 hectares, to the state, more than 90% of the deposit’s reserves became state-owned. This was understood as the state acquiring 90% of the strategic deposit, and thus, no further dispute arose regarding whether Tavantolgoi was a strategic deposit. However, the fact that this agreement was not submitted for discussion and ratification by the Parliament seems to have become a key point for the government today. This is similar to the case with Erdenet Mining Corporation (EMC)’s 49% and the so-called “Dubai Agreement”, where the government made decisions without consulting Parliament, which was argued to be illegal. Nevertheless, if Energy Resources did not submit the transfer of the Tavantolgoi licenses to Parliament and if the government violated the law, the situation would likely revert to the conditions of 2008. According to the current situation, it means that Energy Resources now owns the licenses of ETT. Under these circumstances, the 50% the state is supposed to receive would almost equate to the 50% of the current ETT. It will be interesting to see what move the government makes next.

Ukhaakhudag deposit. The question is whether it is a strategic deposit or the state has the right to own a share. The first six exploitation licenses for the Tavantolgoi group of deposits were granted to Energy Resources in August 2006, as can be seen from the cadastral system of the Mineral Resources and Petroleum Authority of Mongolia (MRPAM). Prior to that, there were exploration licenses, which passed through both foreign and domestic companies until they were eventually owned by Mine Info LLC. Subsequently, Mine Info LLC, together with other investors, established Energy Resources in August 2005 and transferred the exploration licenses of Tavantolgoi to Energy Resources. The company then converted the exploration licenses into exploitation licenses in 2006. This shows that the exploration license for Tavantolgoi was transferred to Energy Resources before the amendment of the Minerals Law. However, it is important to note that before the Parliament’s decision in February 2007 to include the Tavantolgoi deposit as a strategic deposit, Energy Resources already owned the six exploitation licenses for the Tavantolgoi deposit. In other words, it means that the Tavantolgoi deposit, which was owned by Energy Resources, was later designated a strategic deposit by the Parliament, not that the strategic deposit of Tavantolgoi, which was under state ownership, was transferred to Energy Resources. Since it has been designated a strategic deposit, the state must agree on the percentage of state ownership for it to continue operations. Similar to Oyu Tolgoi, Tsagaan Suvarga, and Zuuvch Ovoo. The government and Energy Resources held multiple negotiations in 2007 to determine the state’s ownership share in the Tavantolgoi deposit. At that time, the government’s direction was not to have a stake in Energy Resources but to acquire all of Tavantolgoi’s licenses for the state. As a result, in 2008, a special agreement to transfer mineral licenses was signed, with Energy Resources transferring five of its licenses, excluding Ukhaakhudag, to the state for a nominal fee of one MNT. By transferring 96% of the total area of the Tavantolgoi deposit, or 68,000 hectares, to the state, more than 90% of the deposit’s reserves became state-owned. This was understood as the state acquiring 90% of the strategic deposit, and thus, no further dispute arose regarding whether Tavantolgoi was a strategic deposit. However, the fact that this agreement was not submitted for discussion and ratification by the Parliament seems to have become a key point for the government today. This is similar to the case with Erdenet Mining Corporation (EMC)’s 49% and the so-called “Dubai Agreement”, where the government made decisions without consulting Parliament, which was argued to be illegal. Nevertheless, if Energy Resources did not submit the transfer of the Tavantolgoi licenses to Parliament and if the government violated the law, the situation would likely revert to the conditions of 2008. According to the current situation, it means that Energy Resources now owns the licenses of ETT. Under these circumstances, the 50% the state is supposed to receive would almost equate to the 50% of the current ETT. It will be interesting to see what move the government makes next.

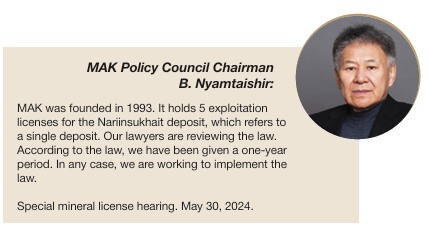

Nariinsukhait and other deposits are in significantly different conditions compared to Ukhaakhudag. In the 2007 resolution of the Mongolian Parliament (Resolution No. 27), which listed the 15 strategic deposits, it was stated that “It is advisable to maintain the current operating conditions of the Tumurtiin Ovoo zinc deposit, Narinsukhait coal deposit, and Boroo Gold’s main gold deposit, which have signed Stability Agreements with the government.” This refers to the companies “Tsairt Mineral,” “Boroo Gold,” and “Qinhua-MAK-Nariin Sukhait.” In the Mining Law, initially adopted in June 1996, it was stipulated that companies investing over USD 2 million should sign a Stability Agreement with the Ministry of Finance for a period of 10-15 years, depending on the level of investment. Under this law, Stability Agreements were signed with specific companies for the operation of the Boroo, Nariinsukhait, and Tumurt Ovoo deposits. One of these companies was “Qinhua-MAK-Nariinsukhait,” a joint venture between the Chinese company and MАK, which was the sole operator at the Nariinsukhait deposit at the time. This company signed a Stability Agreement in July 2005 for a term of 10 years, which was two years before the declaration of the strategic deposits in 2007. “Qinhua-MAK-Nariinsukhait” obtained the special exploitation license MV-005459 for the Nariinsukhait deposit in 2003. The company’s Stability Agreement has now expired, and the mining reserves are also nearing depletion. During this period, MАK took back control of the joint venture. Essentially, this means that the foreign-invested mine was returned to MАK, which subsequently changed the company’s name to “Khuren Tolgoi Coal Mining.” From 1995 to 2006, MАK obtained a total of six exploitation licenses for the Nariinsukhait group of deposits, all of which were acquired before the deposits were designated as strategic. The special licenses obtained by MАK and Energy Resources were granted before the strategic deposit list was announced, and these companies had entered into certain agreements with the government at that time. Therefore, it is evident that the current government has a clear legal basis for negotiating with them again. As for other companies operating in the Nariinsukhait group of deposits, such as Southgobi Sands and Usukh Zoos, they acquired their exploitation licenses after the strategic deposit list was finalized. Tsairt Mineral LLC first obtained the exploitation license for the Tumurt Ovoo zinc deposit in August 1997. This was 10 years before the strategic deposits were designated. Although the Stability Agreement was signed in 1998, its implementation was delayed by two years, starting in 2000. Mining operations began in 2004. The agreement was for a period of 15 years and expired in 2015. Metal Impex LLC initially owned 49%, but now owns approximately 66%. The main shareholder of the company was D. Jargalsaikhan, who was the head of the Mineral Resources Authority at the time.

Nariinsukhait and other deposits are in significantly different conditions compared to Ukhaakhudag. In the 2007 resolution of the Mongolian Parliament (Resolution No. 27), which listed the 15 strategic deposits, it was stated that “It is advisable to maintain the current operating conditions of the Tumurtiin Ovoo zinc deposit, Narinsukhait coal deposit, and Boroo Gold’s main gold deposit, which have signed Stability Agreements with the government.” This refers to the companies “Tsairt Mineral,” “Boroo Gold,” and “Qinhua-MAK-Nariin Sukhait.” In the Mining Law, initially adopted in June 1996, it was stipulated that companies investing over USD 2 million should sign a Stability Agreement with the Ministry of Finance for a period of 10-15 years, depending on the level of investment. Under this law, Stability Agreements were signed with specific companies for the operation of the Boroo, Nariinsukhait, and Tumurt Ovoo deposits. One of these companies was “Qinhua-MAK-Nariinsukhait,” a joint venture between the Chinese company and MАK, which was the sole operator at the Nariinsukhait deposit at the time. This company signed a Stability Agreement in July 2005 for a term of 10 years, which was two years before the declaration of the strategic deposits in 2007. “Qinhua-MAK-Nariinsukhait” obtained the special exploitation license MV-005459 for the Nariinsukhait deposit in 2003. The company’s Stability Agreement has now expired, and the mining reserves are also nearing depletion. During this period, MАK took back control of the joint venture. Essentially, this means that the foreign-invested mine was returned to MАK, which subsequently changed the company’s name to “Khuren Tolgoi Coal Mining.” From 1995 to 2006, MАK obtained a total of six exploitation licenses for the Nariinsukhait group of deposits, all of which were acquired before the deposits were designated as strategic. The special licenses obtained by MАK and Energy Resources were granted before the strategic deposit list was announced, and these companies had entered into certain agreements with the government at that time. Therefore, it is evident that the current government has a clear legal basis for negotiating with them again. As for other companies operating in the Nariinsukhait group of deposits, such as Southgobi Sands and Usukh Zoos, they acquired their exploitation licenses after the strategic deposit list was finalized. Tsairt Mineral LLC first obtained the exploitation license for the Tumurt Ovoo zinc deposit in August 1997. This was 10 years before the strategic deposits were designated. Although the Stability Agreement was signed in 1998, its implementation was delayed by two years, starting in 2000. Mining operations began in 2004. The agreement was for a period of 15 years and expired in 2015. Metal Impex LLC initially owned 49%, but now owns approximately 66%. The main shareholder of the company was D. Jargalsaikhan, who was the head of the Mineral Resources Authority at the time.

The owner of the Boroo Gold main deposit, Boroo Gold LLC, signed a Stability Agreement with the government in July 1998 for a period of 10 years. In May 2000, the agreement was amended to extend the duration to 15 years and increase the investment to USD 25 million. The agreement expired in 2013. Boroo Gold LLC obtained three exploitation licenses for the Boroo deposit between 1996 and 2007. Although the special exploitation licenses for the strategic deposits held by these two companies were granted before the strategic deposit list was finalized, the expiration of the Stability Agreement makes it possible to negotiate the state ownership share legally.

HOW MUCH DIVIDEND ARE THE COMPANIES SEEKING FROM THE DEPLETING RESERVES?

In an interview with the press last September, the Head of the Government Secretariat, N. Uchral, mentioned that by establishing state ownership in the strategic deposits currently under private companies, it would be possible to accumulate MNT 4 trillion in dividend income in the Sovereign Wealth Fund over the next 15 years. Currently, the estimated dividend income from strategic deposits owned by the state or with state participation is projected to amount to MNT 28 trillion by 2040. Additionally, if the state ownership of the 9 deposits owned by the private sector is clarified, the accumulated dividend income in the Sovereign Wealth Fund is expected to reach MNT 32 trillion. It remains unclear which deposits will contribute to the dividend income. However, it is evident that the government has launched this campaign to collect MNT 4 trillion in dividends over the next 15 years. As previously mentioned, the companies operating on the four deposits currently under state agreement could potentially negotiate state ownership and distribute dividends. However, the reality paints a different picture. Most of these companies are unlikely to be able to distribute dividends in the future, and even if they could, the dividends would be relatively modest. The company with the most stable mining conditions and business operations is Energy Resources. With its beneficiation plant and consistent annual production and export, it is well-positioned for long-term operational stability. However, it is important to note that since Mongolian Mining Corporation, the parent company of Energy Resources, became a joint stock company in 2010, it has never distributed any dividends. For companies that have signed Stability Agreements with the government, their exploitation reserves are nearly depleted. “Qinhua-MAK-Nariinsukhait”, now “Khuren Tolgoi Coal Mining,” is expected to run out of reserves by next year and has already announced plans to close the mine. Of course, the reserves of MAK are a separate issue. Regarding other companies operating in the Nariinsukhait coal deposit, some have reserves of 10 million tonnes and extract 100,000 tonnes of coal per year. If the state were to acquire ownership in such companies, it could likely provoke significant criticism. Additionally, according to information on the website of Tsairt Mineral LLC, the initial confirmed reserve of the Tumurt Ovoo deposit is approximately 8 million tonnes of zinc ore. Since the operation of the beneficiation plant in 2005, the company has been producing and exporting an average of around 90,000 tonnes of zinc concentrate annually. While the most recent reserve estimates are unclear, the company has extracted the amount of zinc ore originally established in the initial reserve. The license for the Boroo deposit will expire in two years. According to the company’s website, the deposit has enough reserves to continue operations until 2032, with around 8 tonnes of gold reserves. When mining began 30 years ago, the price of gold was around USD 200-300 per ounce. While the mine had been preparing for closure for over 10 years, rising gold prices made it economically viable to extract ores with lower grades, and thus, mining has continued. Since both the Tsairt Mineral and Boroo Gold deposits are nearing depletion, the government may not pay much attention to the state ownership of these two deposits. However, regarding state ownership in coal mines, it is crucial to approach the issue not only from a legal standpoint but also from an economic efficiency perspective. Given the current decline in coal prices, the rising cost of mining operations, and decreasing profitability, it is uncertain how wise it would be for the state to acquire ownership.

OWNERS OF THE NEXT 60 DEPOSITS ARE PATIENTLY OBSERVING J.ODJARGAL AND B.NYAMTAISHIR

At a time when the government is aggressively pushing to establish state ownership in major national mining companies, those in the mining sector are sitting in silence, as if gagged. This is not the only instance. Over the last 4-5 years, government involvement in the mining sector has sharply increased, with policy changes such as restrictions, confiscations, and sudden decisions being made by the government, which the mining sector has quietly endured. The underlying reason for this seems to be the shrinking size of Mongolia’s mining sector and the near absence of foreign investors. In 2012, when the Parliament passed the “long-named” law aimed at limiting foreign investment, the entire mining sector opposed it. At that time, there were many foreign investors, and several ongoing projects, so the opposition was loud and strong. The Parliament soon revised the law and eventually annulled it. The stock prices of the few companies listed on foreign stock exchanges barely changed. The next reason for the silence in the mining sector is the government’s “intimidation.” For the past 15 years, the government has repeatedly declared that every promising and prosperous deposit discovered would be classified as a strategic deposit, and the state would take ownership. It is no secret that mining companies are “afraid” of this. The Head of the Cabinet Secretariat, N. Uchral, announced, “We will soon update the list of strategic deposits. There are over 60 large new deposits with defined reserves, yet no decisions have been made regarding them since 2007.” In fact, initiatives to update the list of strategic deposits have been made twice in the past. In 2013, the government established a working group and proposed 19 of the 39 deposits listed in the annex of the Parliament’s 27th resolution to be classified as strategic deposits. However, Parliament decided that no action was needed, and it was rejected. Later, in 2018, the Ministry of Mining and Heavy Industry introduced a proposal to include an additional 41 new deposits, but it was sent back for further preparation. It is no longer a secret which deposits fall under these 60. Most are gold, coal, and iron ore deposits. Mining Insight magazine first reported information on these deposits in its September 2024 issue. Most of the more than 60 deposits mentioned above are owned by national companies. Among them, some are interested in starting operations only after being classified as strategic deposits and having the government take an ownership stake. A few hold a quiet hope that they may be able to “negotiate” with the government in some way, while the majority are waiting to see what decisions will be made by Energy Resources and MAK, and what J. Odjargal and B. Nyamtaishir will say. Their actions and negotiations with the government will set a precedent for future strategic deposits. Meanwhile, there are reports that Energy Resources and MAK are aiming to reach an agreement with the government within this year. It is possible that MAK’s negotiations will be presented in the upcoming fall session of Parliament. Whether they will offer shares, pay a special royalty fee based on agreed terms, or resort to arbitration, will become clear in the coming days. In any case, J. Odjargal and B. Nyamtaishir have a compelling reason to engage in effective negotiations with the government. Both have invested in gold and copper projects, in addition to coal, and have expressed their intention to make their companies’ futures less dependent on coal. Therefore, instead of clinging to coal mines whose future is increasingly uncertain, they hope to successfully move forward with more important gold and copper projects in the coming years. They believe that this will not only open doors for new projects in the name of Mongolia’s mining industry but also present a long-term solution for the future of the sector, and they are waiting for the government to engage in discussions.

Mining Insight Magazine, №02 (039)