•Mongolia’s Glass Accounts Law offers unprecedented access to information on the finances and operations of state-owned extractive companies.

•The law’s requirement to disclose individual financial transactions of above MNT 5 million (around USD 1,750) sheds light on state-owned mining companies’ suppliers and buyers, often for the first time.

•Compliance with this requirement improved significantly over the past two years, but many prominent companies still do not report, and some have not provided the required level of detail.

•Scrupulous implementation of the Glass Accounts Law will improve the accountability of state-owned extractive companies and promote a new standard for mining companies in Mongolia and globally.

MOTIVATION AND SAMPLE

Mongolia’s Glass Accounts Law (2014) requires that government entities and stateowned enterprises (SOEs) disclose detailed financial and operational information on a public website. The government’s Glass Accounts portal has since become a focal point for government transparency. However, uptake of the law has been uneven among government entities, and specifically for many SOEs operating in Mongolia. In part, this lack of implementation stems from the law’s ambiguity on who should report, but it also resulted from the government’s inactivity and poor enforcement as well as limited sanctions for those who do not comply. In this paper, I look at one type of reporting by key mining SOEs under the Glass Accounts Law. This is the requirement to publish all transactions above MNT 5 million (circa USD 1,750) on an individual basis, except for salaryrelated transactions. The low threshold set in the law allows for a detailed analysis of the reporting companies’ business, in cases where such information is available. With this analysis, I strive to promote the use of data and reveal the facts for understanding the SOEs’ business. At the same time, the analysis sheds light on the process of reporting and how it could be improved to ensure transparency and enable public oversight of companies that play a critical role in the economy.

Mongolia’s State-Owned Mining Enterprises: A Deeper Look Into Glass Accounts Data Dorjdari Namkhaijantsan Briefing May 2022 2 Mongolia’s State-Owned Mining Enterprises: A Deeper Look Into Glass Accounts Data As such, I have used graphs to visualize the data, so that other stakeholders can use it to answer their own research questions.

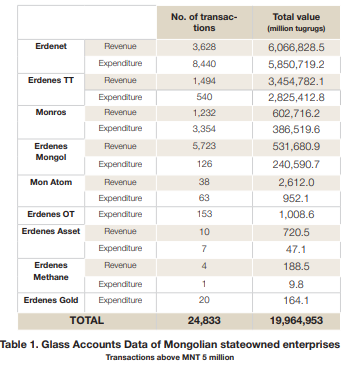

Table 1 lists the nine companies and the total number and value of transactions available under each company’s Glass Account, split by whether the transactions represent revenues (cash inflows) or expenses (cash outflows).

Erdenet and Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi are the two of the largest companies producing and exporting copper concentrate and metallurgical coal, respectively. Monrostsvetmet, a somewhat smaller company, produces fluorspar concentrate and gold. Erdenes Mongol is the holding company and a parent to the other companies included in this sample, except for Erdenet and Monrostsvetmet. The rest are smaller companies under the Erdenes umbrella, aspiring to start projects in uranium, coalbed methane, gold processing and financial asset management. In total, the Glass Accounts for these companies contained 24,833 transactions valued just under MNT 20 trillion, dating back to early 2017. While clearly the number of transactions reported is much higher for the companies operating large-scale mines, the tiny number and trivial value of transactions reported by some smaller companies raise questions about whether these companies have been established prematurely.

TIMELINESS AND COMPLETENESS

I downloaded the data from the government’s Glass Accounts on 9 November 2021.

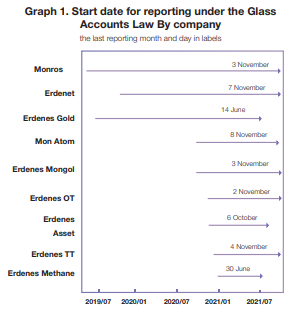

Graph 1 below shows the date when each company began entering data into the Glass Accounts portal. Despite the law becoming effective from the start of 2015, the mining SOEs only began reporting transactions above the MNT 5 million threshold in 2019. Erdenes Mongol, the main holding company, and some of its smaller subsidiaries started reporting only in late 2020. The dates of the final data entry also indicate that companies such as Erdenes Gold and Erdenes Methane have failed to provide up-to-date information over the past five months.

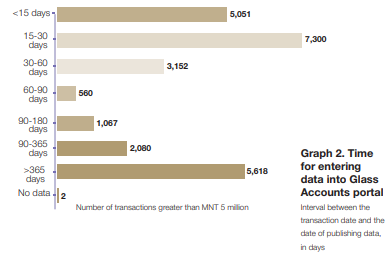

Graph 2 shows the average number of days it took for companies to report transactions in the Glass Accounts. Companies reported the majority of transactions within one month, but many transactions were reported with more than a one-year delay. It should be noted that some companies, for instance, Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, did not initially report because they believed the clause in the law requiring the disclosure of transactions of MNT 5 million and above was only applicable to businesses formally incorporated as SOEs. Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, for example, is a joint stock company. However, as the Ministry of Finance, the manager of Glass Accounts, clarified its reporting templates, uptake of SOEs for disclosure of such transactions improved significantly, including by Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi. The next area of interest is the completeness of data entered by the companies. The requirement is to enter data monthly.

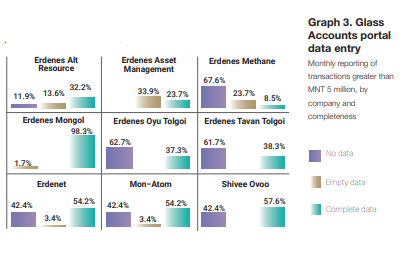

As shown in Graph 3 on the next page, some companies failed to enter any data (the blue bar), while others reported that they entered the necessary information, but in fact the given month’s report did not contain any data (the orange bar). The dark blue bar shows the proportion of transactions for which the monthly data was duly entered. As one can see, Erdenes Oyu Tolgoi, Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi and Erdenes Methane have failed to enter significant portions of data in full.

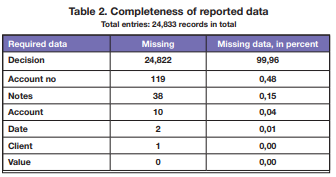

In short, data entry and uptake of the Glass Accounts has been uneven for the nine companies included in the study. In fact, other companies do not even provide any reports, such as the Baganuur coal mine and Oyu Tolgoi copper mine. The companies claim that the law does not apply to them. But Shivee Ovoo, legally the exact same Graph 2. Time for entering data into Glass Accounts portal Interval between the transaction date and the date of publishing data, in days Graph 3. Glass Accounts portal data entry Monthly reporting of transactions greater than MNT 5 million, by company and completeness 5 Mongolia’s State-Owned Mining Enterprises: A Deeper Look Into Glass Accounts Data company as Baganuur, with minority of shares openly traded on the Mongolian Stock exchange, has duly reported under the Glass Accounts. For Oyu Tolgoi, while the government holds minority shares in the company, has long portrayed itself as the most transparent company in the country, but in fact, it has lagged behind SOEs ever since the latter started reporting under the Glass Accounts Law. Turning to the completeness of reports provided, Table 2 lists the required information, and whether it was provided or not. It suggests that nearly 100 percent of SOEs failed to attach a copy of the decision that served as the basis of the transactions, often did not provide the account number and bank account details, and did not provide notes or explanations of the transaction. Given this complete ignorance of the requirement to enter the relevant authority’s decision, we need to understand why companies fail to comply and modify the requirement as needed.

Uneven compliance and data incompleteness partially relate to the technical processes of collecting and disclosing the data, which the Ministry of Finance oversees. Recording data as if in compliance, even when no actual data is available, makes it difficult to track companies’ compliance. In such cases, at least reasons why the company did not provide specific data should be clearly explained. Further, all the reports are downloadable monthby-month, and one can only download the full database through tedious clicking, copying and pasting, or using highly technical code. Therefore, the Ministry of Finance could work on providing options for users to download the data in open data formats to address incompleteness and reduce noncompliance.

TRANSACTIONS IN MORE DETAIL

Now let us turn to the actual data and information that can be helpful when seeking to understand company performance.

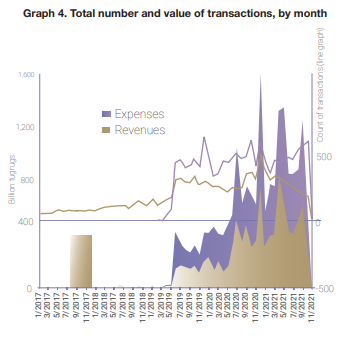

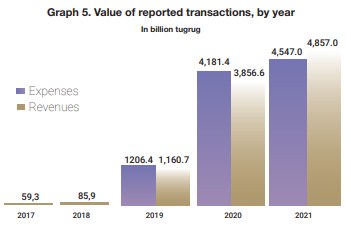

Graph 4 below shows the total value and number of (both expense and revenue) transactions by month of transaction. For the nine companies in the sample, while the actual reporting started in early 2019, revenues dating back to early 2017 and expenses incurred from the beginning of 2019 are disclosed. The total value of transactions peaked in December 2020, then fell rapidly in the first quarter of 2021.

In both 2019 and 2020, reported revenues were lower than expenses, while in 2021 this mini trend reversed, as shown in Graph 5. The SOEs likely benefited from the higher commodity prices in 2021. Next, I dissect these graphs at the level of individual companies. As expected, Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, which operates the larger chunk of the Tavan Tolgoi coal deposit in southern Mongolia and exports all its products to China, and Erdenet, which has almost four decades of experience as a copper concentrate producer, have reported far larger revenues and expenses than other companies. Erdenes Mongol, a holding company for many other SOEs, and Monrostsvetmet, which produces mainly fluorspar concentrate, reported relatively smaller, but still significant transactions.

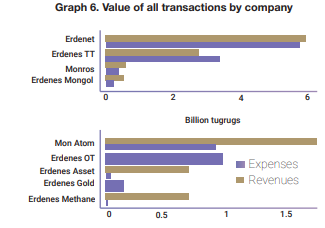

However, the other five companies reported transactions with much smaller value, so their numbers could only be visualized separately from the other four, as shown in Graph 6. Notably, Erdenes Oyu Tolgoi, the minority shareholder in Oyu Tolgoi and partner to Rio Tinto, and Erdenes Gold, which aspires to build a gold smelter and run gold and silver mines, have not reported any revenue transactions in the Glass Accounts. On the contrary, Mon-Atom, which is construct ing a uranium mine together with French giant Orano, Erdenes Methane, which hopes to develop coalbed methane, and Erdenes Asset, which plans to engage in the financial asset management, have all reported expenses equal to less than half of the total revenues they collected.

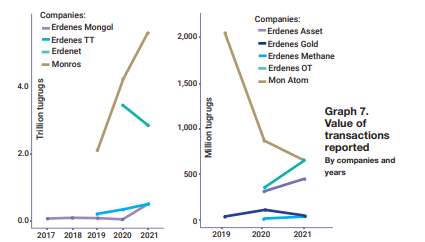

The value of transactions that these companies reported from year to year has fluctuated significantly for companies such as Erdenet, Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, MonAtom and Erdenes Oyu Tolgoi, whereas the value of transactions for other companies remained relatively flat, as seen in Graph 7. For the first two companies, such fluctuations likely reflect changes in commodity prices and challenges resulting from COVID-19-related production and export restrictions. With this general picture of reported transactions, I will now analyze individual transactions.

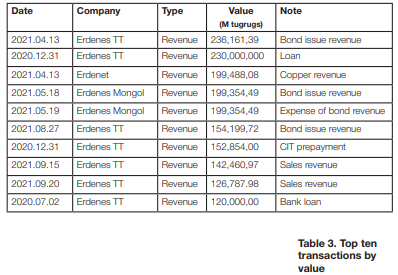

Table 3 shows the 10 largest transactions from the total 24,833 transactions that these nine companies reported, with details on the date, company, type of transaction, value, and note or explanation provided. Interestingly, the largest two cash inflows that companies reported related to money that Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi raised through a bond issuance and a bank loan. On 18 May 2021, Erdenes Mongol recorded a large transaction related to the cash raised from the bond issuance, to only expense the whole amount the next day. These two transactions likely relate to Erdenes Mongol and its subsidiary’s financing of the government’s cancellation of pension-backed bank loans by the elderly. One other transaction that stands out is Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi’s payment of corporate income tax to the government as an advance payment, on the last day of 2020.

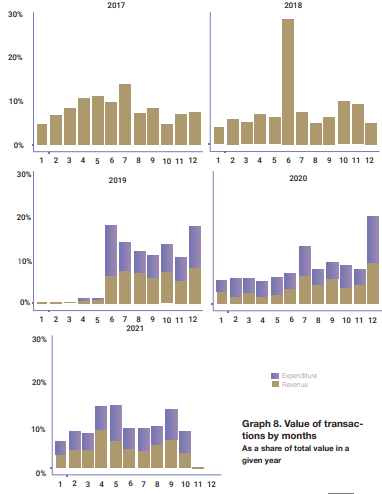

Graph 8 shows whether this has become a trend. In 2020, the value of transactions clearly increased in the last month of the year. Otherwise, the trend is not that obvious. Likewise, one can look at the days of the week when transactions were executed.

As shown in Graph 9, the number of transactions increased toward the end of the week. In fact, 2.1 percent of all transactions were executed on weekends. This could of course be a simple error in reporting, but once again, one cannot determine from the Glass Accounts whether that was the case. Next, I turn to the details of individual transactions. I start by examining who these mining SOEs deal with. First, I look at the banks that facilitate transactions for SOEs and then look at who these companies make transactions with.

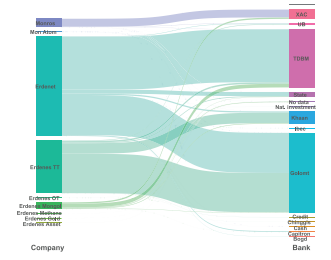

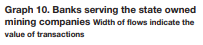

As shown in Graph 10, Golomt Bank and the Trade and Development Bank of Mongolia are the runaway leaders in serving SOEs. Khaan Bank, Xacbank, State Bank and Ulaanbaatar Bank also carry out some transactions. Interestingly, Monrostsvetmet deals mostly through Xacbank, while State Bank’s business with these SOEs is almost solely with Erdenet. Notably, State Bank is the only stateowned commercial bank operating in Mongolia. One can also dig a bit deeper into what companies and individuals were on the receiving end of the mining companies’ expense transactions. It should be noted that the names of the clients as reported under the Glass Accounts represent the biggest data cleaning challenge for users of the data because the names of the same companies are entered in many different ways, without unique identifiers such as the registration numbers of the companies, making it a challenge to analyze individual clients. Therefore, this part of the data review should be treated with a caution, and the government should improve its reporting templates to ensure that companies enter their correct names or business registration numbers, and individuals’ names are also reported in a uniform manner.

Nevertheless, Graph 11 shows the top 15 clients of mining SOEs in terms of the total value of (both revenue and expense) transactions reported by these companies under the Glass Accounts. Unsurprisingly, the largest beneficiary was the government’s treasury, which could be combined with the tax office and finance ministry receipts, which are entered separately and are also in this top 15 list of clients. Other than that, the next four largest clients are likely the commodity traders (Taurus, Milliford, Ocean Partners and King Fine). Red Metall and Samsung Corporation are also likely to be commodity traders, although the latter could also be providing other services to mining operations. Interestingly, Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, one of the companies included in our sample of nine companies, figures as a recipient of significant amounts. While unclear from the data, this might be the result of errors in data entry where the client is indicated as the company itself, or due to inter-company transactions between SOEs in the form of loans and subsidiary payments.

PAYMENTS TO AUTHORITIES, SUBCONTRACTORS AND SUPPLIERS

Now I turn to a more detailed view of the expenses that the nine SOEs reported. It should be noted that while the values of transactions are easy to detect from the Glass Accounts, the purpose of transactions and, as noted above, the list of beneficiaries, are not clearly visible as there is no standard entry form for the data on companies or transaction types. As such, I had to classify the transactions data using my own groupings.

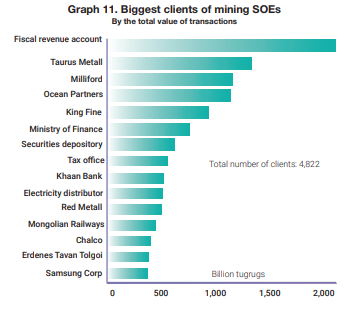

Graph 13 shows the number of transactions for different client types. The largest number of expense transactions were directed to local limited liability companies, whom I have excluded from the plot because they are a clear outlier (most of the businesses are registered as limited liability companies). The next largest group is the payments to the customs in the form of duties and taxes. Also, the companies make many payments to educational and training organizations, presumably paying for training and retraining of employees. They often make payments to individuals (as opposed to legal entities), either for purchase of certain goods and services or as a cash support. Other large volume expense items include payments to companies from China, settlements with the railway, and social insurance payments. This data on the number of transactions is not complete without a look at the monetary value, which I look at next.

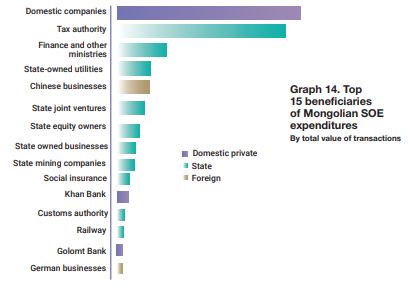

Graph 14 shows the top 15 beneficiaries of the expenses incurred by the companies in the sample, only this time by the value of transactions. Understandably, domestic limited liability companies received the largest chunk of expenses by the nine SOEs. However, one can note that most of the expenses were incurred in relation to statutory obligations of the companies to the state actors, or as payments of services provided by state run companies, such as electricity and other utility providers or railway owners. Subcontractor and supplier service payments to Chinese businesses constitute the biggest cross-border expense for the companies. Khan and Golomt banks were also listed as important beneficiaries of expense transactions. One can also look at the individual companies and agencies that received the expenses by the SOEs.

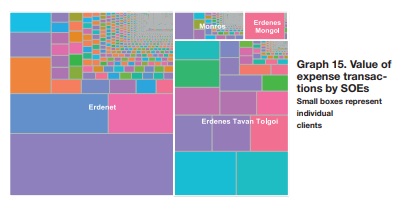

Graph 15 (next page) provides a general picture, with the size of the boxes representing the value of the transactions and the color individual recipients. Notably, this plot could not even show five companies’ expense transactions, as the values of their transactions were trivial. In the plot above, Erdenes Mongol’s expenses went largely to one company, and one can identify this recipient.

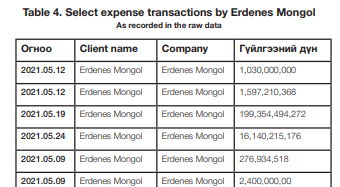

As I checked the data, it appears that some transactions were not properly entered in the first place, as shown in Table 4, and I could not reveal more information by dissecting other columns in the raw data, like the “notes” section.

Once again, the data entry in the Glass Accounts portal creates problems for understanding and analyzing the data, and the lack of clarity around the destination of the large chunk of payments by the main SOE is alarming. As a conclusion to my examination of the expenses, I will show the largest expenses by the SOEs and the service providers and suppliers that benefited from them.

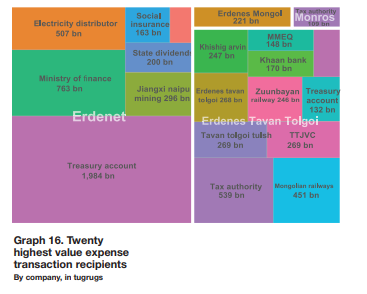

Graph 16 shows that the Ministry of Finance and Tax Authority, as well as stateowned Mongolian Railways and Zuunbayan Railway, which are building coal hauling railways from the large coal mining areas to the border with China, are some of the largest recipients of cash payments by the SOEs. It is noteworthy that these railway projects were directly financed by the SOEs and not through ordinary government budget processes. For Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, TTJVCo and Khishig Arvin are the two of the largest mine operators. For Erdenet, electricity payments and social insurance payments are also significant.

BUYERS OF SOE PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

Now I turn to the revenue side of the SOEs. Erdenes Mongol disclosed revenue data dating back to 2017, while other companies’ data go back to 2019. Notably, the Glass Accounts data is the first time the major mining companies disclose information on the buyers of their products and services, as until now commodity trading has been largely opaque.

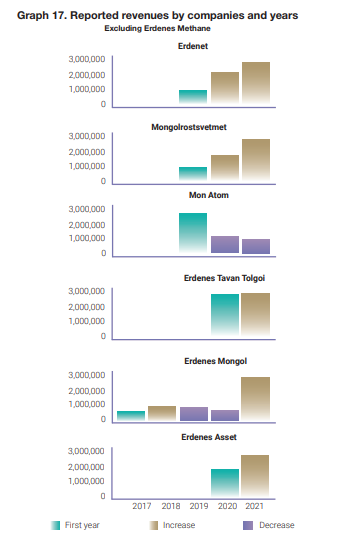

Graph 17 shows reported revenues grouped by companies and years, with colors indicating whether the revenues represent an increase or a decrease over the previous year. Again, the three companies operating large scale mines, Erdenet, Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi and Monrostsvetmet, reported the highest value. While the size of revenue for Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi remained almost unchanged, that of Erdenet and Monrostsvetmet increased significantly. Coal exporting Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi suffered from setbacks with exports to China during the last two years, marred with the pandemic, whereas Erdenet and Monrostsvetmet maintained their production while benefiting from the strong prices for their respective products, copper and fluorspar concentrates.

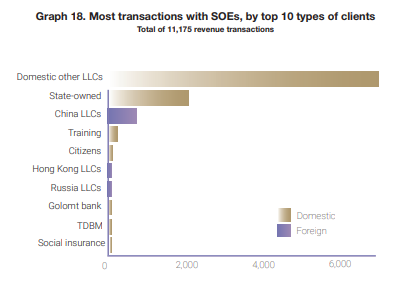

In the next plot, Graph 18, I show the types of clients that made payments to the SOEs most often. As expected, domestic companies are the largest group. However, doing business with other stateowned companies is also quite popular. Chinese, Hong Kong and Russian companies head the list of foreign clients. Interestingly, SOEs receive many payments for training services they provided or for reimbursements of training costs. Social insurance coverage payments and reimbursements comprise the top 10 most popular revenue transactions.

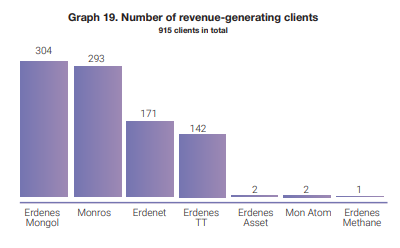

The next plot, Graph 19, shows the number of revenue generating clients for each company. While Erdenes Mongol has the highest number of clients providing revenues to the company, Erdenes Methane has recorded four revenue transactions from only one source, its parent Erdenes Mongol, and Erdenet Asset and Mon-Atom had only two sources for their revenues. Lack of a revenue base for these smaller companies is an issue that Erdenes Mongol management must address. Also, while Erdenes Mongol and Monrostsvetment recorded much lower revenues compared to Erdenet and Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, they dealt with more clients than the latter two. Next, I provide more details on the specific companies and individuals that generate revenues for the mining companies.

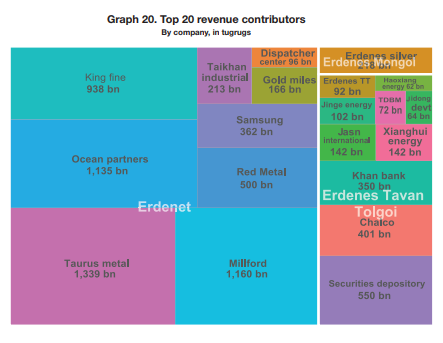

Graph 20 shows the top 20 contributors of cash for the nine SOEs. Erdenet’s partners are the largest in size and are mostly commodity traders buying copper concentrate from the company. Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi received most of its revenue from Chinese companies, but the Glass Accounts Graph 18. Most transactions with SOEs, by top 10 types of clients Total of 11,175 revenue transactions Graph 19. Number of revenuegenerating clients 915 clients in total 19 Mongolia’s State-Owned Mining Enterprises: A Deeper Look Into Glass Accounts Data lists the company itself as the contributor for a sizable chunk of transactions, valued at around MNT 92 billion. For Erdenes Mongol, the receipt of MNT 218 billion from its daughter company, Erdenes Silver Resources, which was likely to be to finance the government’s quasi-fiscal cancellation of pension-backed loans of the elderly, raises questions on whether such transactions that are not related to the main business of the SOEs could harm them by suppressing profitability.

KEY TAKEAWAYS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

After this in-depth exploration of the data, key findings include:

• Mongolia’s Glass Accounts portal is an innovative and far-reaching government effort that, if fully implemented, could allow stakeholders to analyze data, devise reform ideas and engage in oversight of state institutions, with these efforts highly likely to contribute to the performance and effectiveness of the government.

• Application of the Glass Accounts law beyond the government’s budgetary entities to SOEs has proven important given the presence of large number of SOEs, especially in the mining and mining-related sectors, and which play a significant role in the economy.

• Glass Accounts data has become the main source of information on government activities. Civil society and other stakeholders have been actively using the information to monitor specific agencies and SOEs. Such active use of information revealed specific cases of mismanaging public funds, and equally valuably, sparked debates on how the Glass Accounts could and should be improved. I note the emergence of the analysis and tracking of the Glass Accounts, including by certain media and civil society groups that have specialized on such projects on a continuous basis.

• Despite this notable progress, many opportunities remain to further transparency and advance data and evidence-based accountability and policy reforms. Such missed opportunities result in part due to existing processes of collecting and disclosing data through the Glass Accounts, and in part to the quality of disclosed data, especially their completeness and comprehensiveness.

Specifically, the following gaps that could be filled in with relatively little effort: The law’s coverage of who should be reporting under the Glass Accounts is somewhat ambiguous making the reporting uneven across SOEs. SOEs are registered under different legal forms, and the state’s equity participation is uneven across these companies. The most notable companies that the state has the equity participation in and that failed to report under the Glass Accounts include Baganuur coal mine and Oyu Tolgoi copper mine. The former is an openly traded joint stock company with the majority share held by the government, but has not reported its transactions. The same company, Shivee Ovoo, is duly implementing the law. The government holds only 34 percent of Oyu Tolgoi in indirect partnership with Rio Tinto, and this is the most important project for Mongolia on many accounts. Rio Tinto has aspired to lead on the transparency front in Mongolia and beyond, but has lagged behind those SOEs that started to duly report under the Glass Accounts. Data is useful only if it is disclosed regularly and in a timely manner. Some companies did bulk reporting for several years, and some companies do not have the most recent data. Data accuracy is crucial, and the data entry process should be improved. There is no standardized grouping or classification of data, and important variables such as notes to the reported data are not in a form that can easily be analysed. 21 Mongolia’s State-Owned Mining Enterprises: A Deeper Look Into Glass Accounts Data Access to the published data remains a challenge, especially for citizens and stakeholders without advanced computing skills. Disclosures are not always in a machine-readable format, and not easily downloadable for further analysis. The transactions data analysed is missing some important data. For instance, despite being required by the Glass Accounts, the field that should contain data on the decisions that form the basis for the transactions on is left almost universally blank. Glass Accounts lacks data visualization and summarized reports, making it difficult for ordinary people to search for and easily understand the data provided. Recommendations to relevant stakeholders:

• The parliament of Mongolia should continue its leadership in improving government transparency and enforcing existing laws. The Glass Accounts legislation should be further strengthened, specifically by ensuring government officials’ implementation of the law, including ensuring accuracy and timeliness of reports, is linked to their performance evaluations, and the audits of the reporting are done regularly and thoroughly. In addition, legislation should ensure that all SOEs are required by the law to report, regardless of their size, the share of state participation, or legal form. The law also should ensure that all data be provided in the open data format, that is, in machine-readable formats and with an open license for reuse of data for any purposes.

• The Ministry of Finance, as the host of the Glass Accounts, should improve its data maintenance by further investing in the portal and making the data entry and access more streamlined and user friendly. Most data should be entered in a standardized way through specific forms. The data should be downloadable in diverse formats, and the summary reports on the data should be provided with visualizations and details that meet the needs of different stakeholders.

• The National Audit Office should improve its audits on the Glass Accounts, with emphasis on universal and timely reporting and data completeness and accuracy. In doing so, the state auditor should regularly inform the public and civil society organizations and report on whether previous recommendations by the agency have been implemented.

• Industry players and SOEs should actively promote the Glass Accounts and lead by example by including Glass Accounts reporting in their internal processes and evaluation of the performance by the company and the managers. They should also provide recommendations to the government on how to improve the data entry processes and ensure the quality of data. As a final note, Mongolia’s Glass Accounts could be the transparency standard for SOEs not only in Mongolia but also globally. I hope that this report will motivate other countries to improve their transparency practices, especially around extractive SOEs, which often play such crucial roles in their economies.

Mining Insight Magazine №06(007), June 2022