Preparations are underway to update Mongolia's mineral sector regulations, which have remained unchanged for 17 years. Public discussions on the revised draft of the Minerals Law were jointly organized by the Administrative Law Committee of the Mongolian Bar Association and the Open Society Forum on October 19, 2023. The Ministry of Mining and Heavy Industry (MMHI) established the Working Group for the Minerals Law revision on December 25, 2020, and the law's concept was approved on May 4, 2023. The initial version of the project was published online in March 2023, leading to a total of 12 discussions.

During this period, we received 1,315 proposals, including 138 from government organizations and ministries, and 428 from NGOs, both electronically and in writing. The bill that garnered 35 percent of the total votes was uploaded online on October 1. It is proposed that a single law should regulate all solid minerals except for water and oil, including radioactive and widely distributed minerals. The Minerals Law will regulate all activities from uranium mining to gold production. In the draft law, mineral royalty is defined to be paid by the holder of a special license for mineral exploitation and enrichment, the entity exporting minerals, the party selling gold to the Bank of Mongolia, or the commercial bank authorized by it. With the implementation of the Law on Mining Exchange, the mineral royalty will be calculated based on the exchange price in domestic trading. Unlike the current law, which calculates royalty based on an incremental principle, the draft law introduces a fixed tax increase or a specific amount of tax per interval exceeding the base price. As a result, it is expected that royalty will decrease from 19 percent to approximately 10 percent. It's important to note that lawyers and advocates participating in these discussions emphasize that they are providing their observations and opinions on the draft law solely as researchers and experts, not from the perspective of the court or state administration. Among the various topics discussed, this article highlights how the reform of the law addresses the regulation of common court disputes within the industry.

President of the Bar Association Odgerel.P:

Minerals Law Should Cover Industry Regulations

Article 10, Set of Regulations for the Geology and Mining Industry. The mining industry currently encompasses 38 regulations. In the absence of specific regulations, the Minerals Law applies; in the absence of sector-specific regulations, other laws such as the Law on Permits or the Environmental Protection Law come into play. If not addressed by any other laws, the General Administrative Law takes precedence. Essentially, if a particular aspect is not explicitly covered by laws specific to the mineral resources sector, general laws will apply. However, the broader the application of general laws, the less tailored the regulations are to the sector's unique requirements. This can result in reduced legal protection within the industry, as the decisions made tend to reflect the views of authorities and civil servants. Hence, it's crucial to ensure the precision of the Minerals Law. Excessive regulations within the mineral sector are unfavorable. Since the majority of the 38 sector-specific regulations significantly impact the interests of both citizens and companies, it is advisable, whenever feasible, to incorporate these regulations into the Minerals Law. This requirement is also stipulated in the Constitution, which states that 'policies and regulations that affect the interests of entrepreneurs and citizens must be established through legal means only.' Consequently, regulations concerning the revocation of special licenses and other rights should not be determined solely through regulatory measures. The right to engage in activities and personal freedoms should only be limited under established legal procedures. Nevertheless, in an industry marked by constant change, regulations can provide a necessary framework. Presently, not only in the field of mining but across various sectors, regulations have, in some cases, overshadowed legal statutes. This practice persists from the era of socialism when regulations often took precedence over the law. In contrast to the past, our country, which had 50 laws in 1992 and 1998, now boasts a vast body of 800 laws. Developed countries often feature detailed procedures within their laws. Effective management of procedures and decision-making processes is directly linked to reducing corruption and bureaucracy. To combat these issues successfully, it is imperative to legislate and elaborate on decision-making processes. In this regard, close attention should be directed toward Article 10 of the Minerals Law draft and the 38 regulations governing the mining sector.

Chapters 2-7. These chapters address decision-making concerning general special licenses, which encompass exploration, exploitation, enrichment, and control. If the detailed regulation of special permits, including the specific characteristics of minerals, is not outlined in the Minerals Law, the Law on Permits will be invoked The optimal approach would be to integrate the foundational principles of the Permits Law, which encompass the regulation of issuance, extensions, suspensions, and revocations, as specific permit regulations within the Minerals Law, addressing the unique characteristics of the mineral resources sector.

Chapter 8: Significance of VITAL MINERALS. Mongolia's state policy plays a pivotal role in addressing critical matters related to national security and the economy. Given the far-reaching implications and the diverse interests involved, meticulous coordination becomes imperative. To enhance this chapter's effectiveness, it's essential to incorporate state functions. The government should engage in a public dialogue to elucidate the significance of minerals and their connection to national security. The government's policy concerning vital minerals must be transparent, as only then can legal regulations be effectively enforced. A solitary agreement, set of regulations, or administrative act is insufficient. In local communities, disputes often arise between citizens and companies, leading to detrimental outcomes for both parties. It's essential to question the government's role in such situations. When embarking on significant national projects, it is imperative to address the interests of all stakeholders collectively. Failing to accommodate the interests of any party can result in the suspension of mining projects, posing a risk to the nation's progress.

Article 76: Legal Consequences for Law Violators. The regulations regarding legal consequences are perceived as considerably insufficient with only mentions of common laws, such as the Law on Misdemeanors and the Criminal Law. There should ideally be provisions for fines in 10- 20 articles among the more than 400 articles of the draft Law on Minerals. Imposing fines doesn't constitute a punitive measure. Companies engaging in mining activities should be required to acquaint themselves with the Minerals Law and understand the critical aspects to adhere to, serving as a form of precaution. Timely warnings are of great significance for business owners. Providing an opportunity to rectify mistakes without immediate penalties is crucial. Such regulations should be incorporated into Article 76 of the draft law. State bodies, administrative organizations, and professional inspectors should delineate the conditions under which fines are to be imposed when operations should be halted, the circumstances for providing professional guidance, and the timeframe given to rectify errors. In a broader context, it is advisable to encompass regulations on the governance of the mineral resources sector within the Minerals Law. This sector possesses unique attributes that differentiate it from other industries concerning regulatory requirements. Explicitly defining control mechanisms in the law, will facilitate more effective cooperation without overly burdening enterprises.

Munkh-Erdene.T, Head of the Administrative Law Committee of the Mongolian Bar Association:

The procedures for granting, suspending, and revoking licenses have seen minimal changes

Chapter 12: LOCAL RELATIONS. Concept 1.2.11 of the draft law pertains to local relations and community engagement. The inclusion of this concept in the draft law suggests that Chapter 12 contains three overarching provisions for public participation but lacks specific implementation procedures. It remains ambiguous whether cooperation involves employing local residents or engaging local NGOs in their activities. To provide clarity, the law should incorporate comprehensive and explicit regulations.

License. The grounds for decision making by administrative bodies regarding the issuance, suspension, and revocation of licenses have remained largely unchanged. According to Article 56 of the Minerals Law, if a state administrative organization has a reason for license cancellation, a notification is sent to the license holder. The company is then given a specific timeframe to respond and confirm whether they accept the notification. If the company fails to submit the required documents, a decision to revoke the permit is made. In response, the company may initiate legal action against the revocation decision. Notably, the draft law does not introduce any notable changes to this process, indicating that a regulatory framework that has been in place for more than a decade remains unaltered. It is widely recognized that the draft law is rather general, and there is consensus that sector-specific regulations should be incorporated into the law.

Lawyer and Attorney Tuvshinjargal.B:

Current draft fails to address key issues that are the source of extensive disputes

Article 15: Exploration license fee. Article 34.4 of the Minerals Law states, “The payment date for the license fee is determined based on the bank transaction date, and the license fee is considered paid upon the submission of the required documents to the state administration”. It is crucial, especially in the case of extending a special exploration permit, to register the payment receipt with the state administration. This argument raises concerns about the ambiguity of Article 34.4 within the Minerals Law. It leaves a question as to whether the submission of documents must be done in person or if online registration suffices, even when payment is made in cash. Notably, this provision remains unchanged in the draft law, indicating the potential for such disputes to persist in the future. In the aforementioned dispute, the court determined that the grace period for exceeding the payment deadline for the special license could extend up to 30 days. If the payment exceeded this 30- day window, the administrative body could rightfully cancel it due to non-payment. However, the administrative organization proceeded to cancel the license after 1 month, instead of the stipulated 30 days. Upon the cancellation of the special license, the court annulled the decision, asserting that the administrative action did not align with the actual circumstances, as the company had already rectified the violation. An inconsistency becomes apparent when the administrative body decides to cancel the special license the very next day after the 30-day grace period if payment is made, whereas, if the payment occurs two months after the grace period has lapsed, the administrative body refrains from canceling it. This discrepancy is preserved in the draft law. These disputes stem from the lack of clear legal regulations governing the decision-making process of administrative organizations. Given that the law does not offer detailed provisions, administrative organizations formulate internal regulations outlining the application receipt, processing, and the actions to be taken. However, the procedure is not disclosed to the affected party, and it operates like a clandestine norm governing internal organizational issues and labor relations. Consequently, when disputes arise in court, the administrative organization does not substantiate the procedure through normative acts. Despite the substantial number of regulations adopted within the mining industry, there is no overarching provision governing these regulations in the Minerals Law. To address this issue, procedures should be issued in alignment with the law's provisions, and general procedures should be included in the draft law."

Article 14: Exploration License Issuance. The Minerals Law specifies both the timeframe for document submission and the duration necessary for extending a special exploration permit. However, the draft law lacks any provisions beyond stating, "an exploration special permit will be initially issued for 3 years and can subsequently be extended three times for the same duration." This raises concerns about potential arbitrary decisions made by the Ministry of Mining and Heavy Industry or whether MRPAM will approve them. Furthermore, the law reform does not offer clarity on how to address conflicts in the law, leaving questions regarding dispute resolution unanswered.

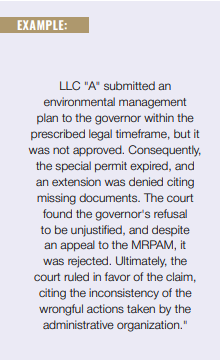

Article 45: Environmental Aspects of Exploration Activities. Owing to the absence of approval for the environmental management plan and nature protection plan, companies often find themselves unable to submit their application for extending the special permit within the legal timeframe. Disputes frequently arise due to the non-approval of these plans by the governor and their absence in the National Assembly. In such cases, the MRPAM contends that the legal framework does not grant the right to extend the special license period, and thus, it should be a matter decided by the court. The court is tasked with assessing whether the actions of the governor and the environmental inspector comply with the law, determining the reasonableness of the refusal, and deciding whether the MRPAM should reinstate the special permit. Consequently, this has led to an increased caseload for the court system. The regulation pertaining to this issue not only remains in the draft law but has become even more ambiguous. For instance, Article 45.5 states, 'If the holder of a special exploration license fully complies with the environmental protection plan, the Governor of the Soum District will refund the money deposited as per Article 44.4 of the Law to the license holder.' Article 45.9 mentions, 'The environmental inspector shall notify the Governor within 15 days upon receipt.' However, the draft law fails to specify who will assess whether the plan has been entirely fulfilled. It lacks provisions for who will oversee and evaluate the implementation of the contentious environmental protection plan. The regulation primarily focuses on refunds of deposited funds. In practice, some companies have encountered challenges when seeking approval for their environmental management plans, with governors delaying approval until after an election, citing local opposition. This has resulted in difficulties between companies, local communities, and NGOs, causing some to withdraw their licenses. Clearly defining the period for plan approval and assessment within the Minerals Law by the Governor could potentially resolve issues that arise among local citizens, NGOs, and companies. Legal scholars have pointed out that the lack of clarity in regulations concerning local relations and the absence of comprehensive legal frameworks for decision-making create conditions for disputes to arise. The mining industry often witnesses numerous conflicts between mining companies and local communities, with the most common dispute being the revocation of a special mineral license, as exemplified by specific cases shared by legal experts. Legal professionals contend that the draft Minerals Law lacks provisions and regulations aimed at preventing disputes and addressing past errors. Consequently, disputes persist due to the absence of a clear sequence of actions. The fundamental model of the decision making process is mentioned in the General Administrative Law, and experts express a strong consensus that the draft Minerals Law should be more comprehensive, with more detailed regulations than the current 400-plus articles.

Mining Insight Magazine, №10 (023)